Have you guys found out about Intersect yet? It's a lovely idea for a social space: you write a story from your life, and mark the time and place. Then you can browse around chronologically, geographically, or both—to see what other stories have happened in that place, or what other stories were happening around the same time. It's engaging, encouraging, and totally addictive. Here's a map of my stories so far—I've been meaning to add more, when deadlines are not breathing like dragons down my neck.

Nathan Rabin Fails at Modeling and as a Human Being.

It may seem like a clever move to self-deprecatingly refer to your own article as a "lousy blog post", but it doesn't mean the phrase does not ring true. If there is one set of ads I would purge from all the internets given the chance (and the POWER), it is the marketing campaign spat forth by American Apparel. They look like the stalkerish photos taken by serial killers and kidnappers, or else they have contorted models into poses that look not merely painful but even injurious, or else they have weird classist vibes that I try very hard not to ponder at any length. They are train wrecks, and so naturally I can't not look at them.

Which is also why I read Nathan Rabin's recent AV Club post: "Death by sexy: a middle-aged man in an Eat Pray Love promotional T-shirt auditions to be an American Apparel model."

I thought there might be some small bit of revelation in it, some piece of information that could illuminate a corner of the world. And there was, but not in the way I wanted.

Our Author dresses in his worst clothes. He makes fun of the female models while praising their looks, and ignores the male models entirely. He describes the aesthetic of AA ads as being uncomfortably close to child pornography, but appears to have no problem finding this sexually appealing. He talks at length to one hopeful model in particular -- and this is where my bit of revelation comes in.

Martha (a pseudonym) is seventeen, and has been modeling for four years. Let that math sink in a little bit. She is described as "Giddy with the hubris of youth," but she's not the one throwing Greek tragedy terms around and attending modeling auditions as a whimsical prank.

No, Martha is here to get paid. She doesn't model full-time, as she's soon to be a senior in high school, but her mom's been unemployed for two years and modeling helps pay the rent every month.

Let's be clear: this girl is helping keep a roof over her family's head.

Mr. Rabin doesn't care.

He wants to talk about her photos:

She then rifled through her portfolio. It was remarkable how different she looked in each photo. Her fresh-faced, well-scrubbed look of pure Americana was eminently mutable. It was as if her face and body were unformed and unfinished and could only be completed by a stylist and photographer fitting her into their predetermined vision. She could be whoever they wanted her to be.

In short, she's a good model. This is her job. Our Author, who is in no financial straits himself and who has already admitted his own inability to look like anything other than what he is (a writer), nonetheless feels perfectly comfortable looking down on this girl:

She noted sadly that Abercrombie & Fitch wanted to buy one of her photographs, but she didn’t have the rights to the photos they wanted to buy; those were held, I suppose, by the photographers who took them or the modeling agency or the clients that bought them.“Shit, man. I could have been an Abercrombie & Fitch model,” she muttered.

I tried to console her. “Eh, I’ve done a lot of campaigns with them. They’re not so great.” But she did not pick up on my sarcasm.

This girl is hard up. She is at a crossroads of several systems that have let her down: the crappy economy, the copyright system that allows other people (very probably male people) to hold the rights to images of her body, images that could have eased the financial burden on herself and her mother.

Meanwhile, over in the Land of Astonishing Narcisissm, Our Author is sad she doesn't laugh at his joke.

This erasure of Martha and her human experience is a colossal failure on the part of Our Author, both as a writer and as a human being. The whole post started with this paragraph:

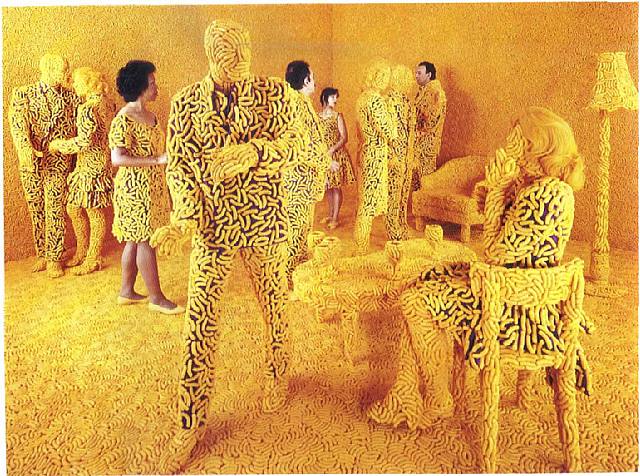

It’s hard not to be moved by the print ad’s haunting images of desperation and sadness. Who were these emaciated young people with their gaunt flesh squeezed into gold lamé leggings, their dead eyes pleading for mercy and compassion? Why did a major chain choose advertising redolent of child pornography from the '70s? Were these runaways all right? Had Charney forced them into lives of prostitution, drug dealing, and pornography? Should I purchase American Apparel clothing, or report its owners and advertisers to the proper authorities?

There seems to be some acknowledgment here that American Apparel models are victims of systemic failure. And -- how lucky for his story! -- the intrepid journalist's impression that AA models look desperate and hungry proves to be actually true in real life. This narrative arc should write itself: "I thought Americal Apparel models looked desperate and exploited -- turns out, they are actually desperate and exploited."

But Our Author seems to forget all his concern for these models as soon as he actually meets on in person.

Is that whole early paragraph just a joke? There is a huge disconnect between Our Author's empathetic response to the pictures early on, and his total disregard of Martha (not to mention all the other models auditioning, who barely rate a description). What exactly is supposed to be the purpose of this piece? Rabin claims that he "wanted to experience the weirdness of an open call for American Apparel models firsthand." But we don't hear about anything particularly weird -- unless your definition of weird includes Nathan Rabin, a bald white dude who likes movies.

This is what happens once Our Author's number gets called for the audition:

The gentleman strained mightily to force a smile and nervously asked, “Do you have any questions for us?”

Yes! Now was my chance to uncover the location of the underage models being kept in cages and forced to be sexy 20 to 23 hours a day! I was in a position to demand answers! I was going to take this whole house of cards down with me and expose the shocking, scintillating, titillating truth.

But “Uh, no, I guess not” was all that came stumbling out of my mouth.

It's funny because . . . because exploitation is funny? Because women in cages are funny? Because a journalist failing to be a journalist is funny? Because there is a gap between Our Author's lurid imaginings of being a writerly hero rescuing sexy teens and his actual ineffective behavior? Because disappointment on every level is hilarious, apparently?

At press time, the most recent comment was: "Nobody cares and this is a shitty story." Which sums it up pretty well.

Rules to Write By/Rules to Drink BY

It is summer, I just got married, and I am a writer, so lately many of my days involve A) drinking, B) writing, or C) both. Lucky me! Lately everyone has advice about these activities! First, there is the NYT essay, which is delightful -- and now, a Jezebel article, which makes me want to take issue with a couple of the points they obviously think are hilarious.

Full disclosure: at present, I am writing this and also drinking some delicious local wine. Plus that Dry Fly gin and tonic aperitif before dinner. So, hey! Drinking and writing!

To begin, the New York Times.

Honestly, I've read a lot about wine, and booze, and history, and the history of wine and booze, and literature about wine and booze, and so on. I am totally behind Geoff Nicholson's point that fictionalized drinking (or history of same) is more fun than instructions on drinking correctly tend to be. (And hey! I had a recent post on that too!) His connection between drinking advice and writing advice strikes me as witty and revealing. In sum: I liked it, and have nothing besides more uninteresting praise to offer.

And now: the Jezebel article.

I read it. And the arguments marshaled themselves and marched full-tilt in the direction of this blog. This may get pedantic, but if I don't let it out my head will explode, so in the interest of, um, not-explodey, here goes:

1. The article's thesis: "This article makes an insightful connection between the uselessness of drinking advice and the uselessness of writing advice -- let's reduce this to a series of pithily described drinking games! Because writing a great work of literature ourselves would take too long."

2. The David Foster Wallace game could easily kill you. Seriously, ten pages or less.

3. Jane Austen: In college, some friends and I came up with a drinking game for the film version of Sense and Sensibility: drink whenever someone dies; drink whenever it rains; drink whenever Fanny says something horrible; drink whenever an engagement is announced; drink whenever Marianne cries; drink whenever someone mentions the letter F. We poured homemade wine into thrifted tea cups and sat back. Twenty minutes later, we had to slow the game. I did not go to the partiest college, is the upshot here.

4. Jezebel knows nothing about Sappho. "Hot or disgusting"? That's the best you can do for the foremost female writer of the ancient world? I mean, yes, there's the "don't prod the beach rubble" fragment, but that's way more poetic in the original Greek, and the few complete poems we have are just stunning . . . (rambles on about love triangles and splintered selves until everyone moves on to the next in the list . . .)

5. Or Homer: ancient Greek wine was thick and hugely alcoholic, like port or vodka if you could make vodka from grapes. It was watered down with strict proportion so that it resembled the red wine we know and love today. People who drank unwatered wine were barbarians, and not worth talking to, much less drinking with.

6. Or Twilight: seriously, there's not nearly enough blood-drinking in Stephenie Meyer for this rule to result in any drinking game worth playing

7. Any James Joyce drinking game is hilarious.

7. Any Dylan Thomas drinking game is in the poorest of poor taste.

RITA: Kinsale, Kinsale, and Chase

I've been going strong on my RITA reading, but somehow or other (wedding, honeymoon) have fallen behind on the actual writing-up of my thoughts. So this post is going to tackle two RITA winners -- plus, a bonus book! -- for reasons that should become obvious. Ultimately, what I've taken away from these three books is: location, location, location.

First up: The Sandalwood Princess, by Loretta Chase.

Brief admission: Loretta Chase is currently my number-one favorite romance author, and for the past year and a half I've been reading everything of hers I could get my hands on. This one was a new one, and unlike many of her others it moved around a lot from place to place: India, onboard ship, a country manor house, and India again.

Brief admission: Loretta Chase is currently my number-one favorite romance author, and for the past year and a half I've been reading everything of hers I could get my hands on. This one was a new one, and unlike many of her others it moved around a lot from place to place: India, onboard ship, a country manor house, and India again.

From a writers' craft standpoint, each of these locations provided a framework for a different part of the story:

- India holds the initial moment of contact, where the thief-hero steals the titular princess statue from our heroine. But it is also the home of the sly, elderly whose failed long-ago romance is the impetus for the plot, and a foil to our hero and heroine.

- On the ship back to England, our hero masquerades as a servant, a deception which succeeds but which does not prevent the heroine from stealing the statue back from the false master she believes to be the real thief. It is also a space where neither the hero or heroine is entirely at home, and being jarred out of a familiar setting leads to more intimate conversation than each might otherwise have permitted.

- Once in England, the heroine realizes the statue is missing and follows the heroine north to find an opportunity of stealing it back -- which means convincing the heroine he was fired by his master once the statue disappeared from the ship. She hires him as a secretary/butler, which allows them to spend hours together in a cozy domestic setting, enjoying one another's company and falling even more deeply in love.

- The thief ultimately has to steal the statue back, for some reason, and everybody goes back to India, where the final twist is revealed and both romance plotlines find a resolution.

Ultimately, the locations are a shorthand for the developing relationship, as often happens in romances (I'm looking at you, Pemberley, and every manor house descriptive passage you've inspired in two hundred years). It's usually a pretty good trick, even when the seams show.

But it has a downside: it can make your hero and heroine seem like they are an entirely different person when they are in a different location. Sometimes this is important, and can shake up a complacent character -- again, PEMBERLEY -- but sometimes it just starts to feel a bit whiplash-y for the reader. "Wait -- who the hell is this person with the same name as that person I was just getting to know? That person would never do this. What's going on?"

Unfortunately, this is what happened in The Prince of Midnight by Laura Kinsale, which was absolutely jam-packed full of things. Anything that could be made interesting was interest-ified within an inch of its life.

The hero is a half-deaf hermit and former highwayman still wanted in England, whose best friend is a tame wolf. The heroine is the only survivor of a family wiped out by a malicious pastor's oppressive cult in her home village. (No, really.) They meet the totally squicky Marquis de Sade, and later a group of aristocratic snuff enthusiasts -- and, to clarify, not the "Oh look at my tiny dandyish habit" snuff. The "Oh look at me choke a woman to death during sex" snuff.

But I'm getting off-track.

I stumbled upon another Kinsale romance, An Uncertain Magic, which had the same rampant busyness. (Psychics! Repressed memories! Revolution in Ireland! The Sidhe! An adorable brandy-drinking pig!) What's more, it had the same unconcern with locations as the first one. Kinsale's places feel ephemeral, as though the characters are only tangentially rooted there. Perhaps this is because the couples in both novels are somewhat unrooted themselves: there's a lot of things that happen on the road, or in houses being falling down or being rebuilt, or in inns and waystations and the like. And I have to admit to being really, really fond of the hero from Prince of Midnight, mostly on account of how different he is from the usual alpha hero. (Very broken, and more than a little sad, and very aware that his desperation is not attractive, which paradoxically makes him quite attractive as a character.)

And maybe it's something about the way the two authors (Chase and Kinsale) think of characters. Chase's style is a much more invisible thing, a mostly realistic narrative voice. Kinsale, though, is a little more fluid and suggestive, a little more poetic, which can be very effective but which always kind of reminds me of Terry Pratchett's description of reading the human mind as "trying to nail fog to the wall." You get all these rich and evocative phrases, but the thread of a specific character's personality tends to wax and wane, disappear and reappear.

Frankly, much as I love an evocative phrase, I want to keep my writing as rooted as possible. Maybe when I make it through all the relevant RITAs I'll start by taking apart a particularly admirable scene or two from some of my favorite novels. Hey, who ever said a comparative literature degree couldn't be useful?

Women Like Writing, But Nobody Writes Like Women.

Internet personality quizzes are my Achilles heel. I enjoy finding out what interval best embodies my complex individuality (major 7th, as it happens) and what the shape of my letter A's says about me on a fundamental level. If I'd been around in the late eighteenth century I would have been totally into phrenology, though it pains me to admit it. But there's something eternally seductive about the idea that my self is just a code waiting to be decrypted. I'm always looking for the key. So when Twitter alerted me to the existence of I Write Like, I jumped all over it. Into the machine went my favorite part of a blog post on my recent honeymoon in Helsinki.

Um, really? I tried again, with a snippet from my rant about Red Dead Redemption.

This was going from bad to worse. I broke out the big guns. And by guns I mean penis -- I put in the steamy sex scene from my historical romance work-in-progress.

Obviously I should be working on a Cthulu love story. As Maggie Stiefvater said, "Kraken are the new vampires."

But wait. I had put in a sex scene -- and a very purplish one, at that. We've already seen Dan Brown's name, and someone else on the internet has gotten Stephen King, so modern (male) genre authors are totally bring-uppable. Is Lovecraft really the closest thing this site could get to a romance author?

Online I found an excerpt from Danielle Steele's The Journey, and put in a goodly chunk of text.

At this point I was getting a horrible feeling that whoever built this site did not think women could write anything significant, memorable, or worth imitating.

Of course, modern romance authors are still kind of ghettoized, sure. So I went classical, and pulled the start of chapter 38 from Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. The one that begins, "Reader, I married him." Who does Charlotte Bronte Write Like?

Like hell she does. (For one thing, she lived about a century earlier than Joyce.) I put in the opening paragraphs from the same book.

At this point I started to go a little crazy, throwing anything and everything into that damn white frame on the site and growing increasingly sure that my outrage was more than just a figment of my imagination. Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own:

Virginia Woolf, Orlando:

By analogy, then, I write like Virginia Woolf, I guess, but this thought was merely a damp handkerchief against the vast Sahara of my frustration as I kept going.

A poem from Emily Dickinson:

Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale:

Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth:

If you've noticed there's an elephant in the room, sipping tea and wearing an empire-waist gown and arguing that the choice of who to marry is screamingly important when it's the only real choice you get to make in your entire life, you're correct. I'd been avoiding putting anything by Jane Austen in here, because honestly it would break my heart to see Jane Austen writing like James Joyce, or Dickens, or frakking Lovecraft. But the question had to be answered.

Jane Austen's beautiful, perfect opening scene from Pride and Prejudice:

Okay, that passage is pretty famous. I kept going.

Persuasion:

Emma:

Mansfield Park:

Northanger Abbey:

Sense and Sensibility:

In conclusion: no female author has ever produced anything important unless they are Jane Austen.

A sly thought occurred. I went back to the Gutenberg Project, and looked up the truncated and very sarcastic History of England that Austen wrote in her youth. I entered this passage:

"The Character of this Prince has been in general very severely treated by Historians, but as he was a YORK, I am rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable Man. It has indeed been confidently asserted that he killed his two Nephews and his Wife, but it has also been declared that he did not kill his two Nephews, which I am inclined to beleive true; and if this is the case, it may also be affirmed that he did not kill his Wife, for if Perkin Warbeck was really the Duke of York, why might not Lambert Simnel be the Widow of Richard. Whether innocent or guilty, he did not reign long in peace, for Henry Tudor E. of Richmond as great a villain as ever lived, made a great fuss about getting the Crown and having killed the King at the battle of Bosworth, he succeeded to it. "

Damn it.

RITA: Mary Jo Putney's 'The Rake and the Reformer' (and 'The Rake' Again)

Another week, another RITA Award-winner to analyze.

Today's book is Mary Jo Putney's The Rake and the Reformer, the winner of Best Regency Romance in 1990. I hadn't read this one before, which means it's harder to pick out the details of technique. One thing, however, leapt right out at me: these characters felt like adults.

It's hard, in the world of the Regency romance, to get characters that feel like grown-ups. Luckily, the trend of the youthful, untouched 18-year-old who enlivens the older, jaded man is fading into the background -- hearts, Madame Heyer godsavethequeen -- but it still lurks in a lot of the structure.

I'm not the only one who noticed this aspect of the book. The notorious Mrs. Giggles said as much in her review: "oh, those days when heroines don't behave like ten-year olds!" But it's a thing that is very hard to pinpoint and emulate, much as I would like to. How do you quantify such a thing? The impression must be made in a series of tiny moments, well-placed words, and vividly well-drawn scenes. It requires a prodigious imagination, an astonishing amount of work, or -- this is the most likely -- both. It is a great achievement.

Mrs. Giggles' review brought something else to light: there are two editions of this book. I've read the earliest -- the Signet edition depicted to the right there -- but La Giggles has obviously read the re-release, and has this criticism to offer: "Reggie doesn't act like a jerk. But isn't he supposed to be a jerk?. . . Reggie is portrayed too nicely and too sympathetically."

Um -- really?

Because about halfway through the book, Reggie -- our hero, who is a full-on alcoholic with blackouts and health troubles -- lapses from his planned sobriety, gets roaring drunk, and tries to rape our heroine, whom he's already on mutually-consented-to-kissing terms with. Some choice phrases he uses during this scene: "Coyness don't suit you, Allie. I know what you want, and be m-more than happy to give it to you . . . Don't you think I know why you're always twitching around me? Underneath that proper face you're as hot as they come, and we both know it." And Allie is horrified and ashamed and fearful but not so fearful that it prevents her from hitting him with any number of heavy objects and yelling and fighting him off. And remember, this is halfway through our romance.

Reading this scene, I felt it was pushing the envelope -- or else it was harkening back to the not-so-long-ago days of Sweet, Savage Love and that one romance novel I read where the heroine was raped by Wagner. (Yes, THE Wagner. It was strange.) And because it was scary, and dangerous, and unprovoked, and mean, it raised the stakes like they rarely get raised for rakes these days. Every frequent romance reader knows that the dangerous rake with the dastardly reputation is not really that bad, deep down. A heroine's reputation may be ruined in the course of the book by her association with the hero, but usually instances of actual, honest-to-goodness abuse are limited to emotional distance and a slight coolness soon shattered by the Sexy Sexy Times the hero and heroine insist on having at intervals convenient to the narrative.

Reggie, on the other hand, is actually, physically, emotionally dangerous. He may well be a terrible choice as a lover, and not simply because Allie's reputation may suffer. She has a strong incentive to not want to spend time with Reggie ever again, after this incident. Of course, they end up happily -- but Ms. Putney makes it a plausible ending, which Reggie has to earn and work toward. Which means, naturally, that this scene's location in the exact center of the novel is no coincidence, but rather a canny bit of planning on the author's part.

Yes, there are plenty of moments where Reggie is otherwise proved not as bad as reputation would have it, but it does matter that we have this particular scene played out with no other witnesses, just Allie and Reggie -- and the reader.

At least, the reader who gets the Signet edition. When romances are reissued, it is not uncommon for the author to also take the opportunity to rewrite them, just a little bit. A book is never really finished, not even for novice aspirants like myself. And these are people Ms. Putney spent a lot of time with when she created them, which the reissue allowed her to revisit and relearn. Mrs. Giggles' opinion that Reggie was too sympathetic either indicates that her standards of villainy are far more demanding than mine -- or else quite a bit of the book was revised when it was put out under the shortened title, The Rake.

What I want to know is this: did she change anything about the near-rape in the reissue? The cheap copy I found on the interwebs should tell me: further bulletins as events warrant.

RITA: Julie Garwood's The Bride

My first form-specific look at a past RITA award winner: The Bride, by Julie Garwood. First off, I must explain that this is one of the first romance novels I read growing up. And it is definitely the one I've reread most often: probably upwards of a hundred times, easily. There are scenes and sentences here that are now part of the physical makeup of my brain.

So learning that it was a RITA winner was a delight, but no surprise. What's more, the book holds up surprisingly well considering it's now old enough to order alcohol (should the book decide it wants a cocktail). But I'm not here to review the book -- I'm here to look at how it's written.

So:

In the forward to my copy, a reissue, Garwood explains that "experts" advised her to leave the humor out of her story: "I had tried my best to follow their advice for a couple of books, but with The Bride, I simply couldn't help myself . . . I finally gave in to the urge and wrote the story as I saw it."

Nor is this the only writers' rule that Garwood breaks in the book. How well do I remember the switches of POV (point-of-view, for you rookies out there) that drive not only the humor, but the developing romance. Like so, when our heroine Jamie learns at the last minute that she is to marry Scottish laird Alex Kincaid at the king's behest. We begin with our hero:

She still hadn't caught on. Alec sighed. "Change your gown, Jamie, if that's your inclination. I prefer white. Now go and do my bidding. The hour grows late and we must be on our way."

He'd deliberately lengthened his speech, giving her time to react to his announcement. He thought he was being most considerate.

She thought he was demented.

Jamie was, at first, too stunned to do more than stare in horror at the warlord. When she finally gained her voice, she shouted, "It will be a frigid day in heaven before I marry you, milord, a frigid day indeed."

"You've just described the Highlands in winter, lass. And you will marry me."

"Never."

Exactly one hour later, Lady Jamison was wed to Alec Kincaid.

According to the hundreds of writing how-to guides out there, this is wrong. Supposedly, to jump from one character's POV to another is confusing and leads to the reader gripping their head in pain and yelling AARGH and throwing the book against a wall and who will give you royalties then, hmm?

But I love and remember and admire the passage above, and every other similar passage in the book. Romances written entirely from one character's perspective (in the vein of a lot of the novels of Georgette Heyer godsavethequeen) aren't as appealing to modern readers. We like being in the hero's head; we like it when he's not some giant impenetrable mystery figure. We want him to be a person, with thoughts and worries and emotions, like the heroine is and has always been.

At some point, if you are writing a romance novel, you are going to have to switch POV. Mostly this happens between scenes, and the general rule is that once you start a scene in one character's POV you stick with that character until the scene break. But if you do it mid-scene, like Garwood, if the reader sees what the heroine above is thinking while the hero's thoughts are still echoing in the reader's -- oh, who am I kidding -- in her memory, you get a moment where it feels like there is a point of contact between the mind of the hero and the mind of the heroine. A moment where Alec's and Jamie's experiences seem to touch, unbeknownst to them, through the medium of the reader.

This is a powerful tool, and it is clear that the reason the how-to guides recommend against it is because such power could spin out of control in the hands of a novice writer. The POV switch is a tool to be used with restraint -- like garlic. Delicious, even occasionally necessary, but repellent when overdone.

The switches in The Bride are primarily used to jump between the hero and the heroine, but not exclusively. Secondary characters get a lot of play, too, which is a neat way of solving the perennial problem of the Infodump. By the time we get a few chapters in, we know how our main characters think about themselves, and about each other, and we also know how they seem to the other people around them. Handy for things like physical description and background info, but for the romance it's just as important to know that Jamie's view of herself as capable and talented is borne out by the opinions of several people around her, even when Alec himself hasn't been convinced yet.

In fact, because Garwood allows us to flit from one character's consciousness to another, she has the luxury of beginning from the POV of Jamie's father:

They said he killed his first wife.

Papa said maybe she needed killing. It was a most unfortunate remark for a father to make in front of his daughters, and Baron Jamison realized his blunder as soon as the words were out of his mouth. He was, of course, immediately made sorry for blurting out his unkind comment.

As a side note, beginning with a secondary character before proceeding to the hero/heroine is a technique frequently used by Jane Austen, most notably in Pride and Prejudice (Mrs. Bennet), Persuasion (Sir Walter Elliot). Garwood's opening technique has a sterling literary pedigree.

Lesson Learned: Rules are made to be broken.

Ready to Read the RITAs? Right!

In more than one bookstore, you can find lists of Hugo and Nebula award winners posted in the science fiction/fantasy sections. Displays of the recent Pulitzer winners are currently everywhere. Man Booker Awards, American Book Awards, National Book Awards -- these will all be noted on shelf cards or pointed out. The reason for this is simple: a good way to sell books is to convince people of a book's importance and quality. Winning a prestigious award is a shorthand for both -- plus, it makes the reader look sophisticated and intelligent when trying to hit on other humans. You know what I have never seen in an actual brick-and-mortar bookstore? A list or display of RITA award winners (formerly known as the Golden Medallion). It's the romance genre's most prestigious award -- which critics will argue is like frosting on a shit sandwich. And hitting on someone when you are holding a romance novel -- drenched fatally in pink and white, or else covered in cursive lettering, or else lounged upon by a scantily clad and heavily haired couple who may in fact be orgasming as you watch -- well, it just plain does not work. The prime cultural tone associated with romance novels is desperation, the antimatter to seduction.

Of course, this is absurd, as anyone familiar with the fine work done over at Smart Bitches, Trashy Books can tell you. Romance readers are smart, and romance is no less powerful a genre than fantasy or science fiction or mystery. It has a craft, and a history, the same way any subset of literature does.

Many of you already know I've been trying my hand at writing romance, which has turned out -- surprise! -- to be hard. It's also amazing, and now that I've started I don't think I can ever stop. It has begun to rewire my brain: everything becomes a potential narrative, the start of a story I haven't learned how to tell yet. And I'm getting better -- but slowly. It is time to take a more organized approach.

Which brings me back to the RITA Awards.

From henceforth, I will be going through the list of RITA winners (focusing on the historical and regency categories, which were once the same but are now separate) and writing about each. This is not going to be merely a process of review -- there are plenty of very thorough and delightful review sites out there already (hello, Mrs. Giggles!). What I am going to be looking at, specifically, is the way the romance is written: the plot setup, the prose craftsmanship, things that leap out from a writing perspective. There will probably be many swearwords.

From henceforth, I will be going through the list of RITA winners (focusing on the historical and regency categories, which were once the same but are now separate) and writing about each. This is not going to be merely a process of review -- there are plenty of very thorough and delightful review sites out there already (hello, Mrs. Giggles!). What I am going to be looking at, specifically, is the way the romance is written: the plot setup, the prose craftsmanship, things that leap out from a writing perspective. There will probably be many swearwords.

One of the reasons for this is a piece of writing advice I've been thinking about a lot lately: never switch from one character's POV to another. This makes good sense, mostly, because leapfrogging around from brain to brain tends to give unpolished prose a feeling of whiplash. But I keep remembering my favorite moments from Julie Garwood's The Bride, one of the earliest romances I read and in fact the first RITA winner for Best Single Title Historical. And many of those moments -- which are hilarious -- depend upon a deft switch from one character's perspective to another.

So sometimes the rules need to be broken, apparently. But we knew that. What other rules can I break, in useful ways? What rules are holding me back, or helping me tell a better story? I intend to learn from the best.

First up: The Bride by Julie Garwood (Best Single Title Historical, 1990).

After that: The Rake and the Reformer by Mary Jo Putney (Best Regency Romance, 1990).

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 8

It would be remiss of me to approach so near National Grammar Day without bringing up punctuation. Punctuation sometimes seems like the appendix of the body of grammar, because oftentimes you can eliminate it entirely and still make something worth reading (I'm looking at you, James Joyce). But in reality it's probably something more like the spleen or gallbladder: you can get by okay without it, but things tend to run more smoothly with it in place.

I think what I like so much about this sentence from the Practical is its sheer hypocrisy: look how many parentheses are there!

The other fun thing about punctuation is that it has drastically, visibly changed over the language's evolution. For instance, Jane Austen's most famous sentence: It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. Note that comma after acknowledged -- nowadays we would leave that sucker out in the cold to die. But Jane Austen thought there should be a pause there, and so in the comma went, to signal a breath in the middle of what is otherwise a bit of a mini-marathon: It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

Butler is having none of this:Jane of course was writing at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and Butler at the end of it. This century saw sweeping changes in not only the literacy rates but in the way reading was approached. Austen's time was still very rooted in oral culture. Letters were important, but were often read aloud to the family as a whole, and conversation was considered an art that required training and rules and delicacy. By the end of the century, however, writing (in the form of newspapers, magazines, and so on) had become the unquestionably central cultural medium. Butler, in his grouchy Victorianism, considers the rules of grammar and syntax a greater good than the actual behavior of words in a human mouth.

And, to fully illustrate the gap between language written and language spoken, here is Victor Borge's Phonetic Punctuation:

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 7

Alas! I have little time today. So I'll post on something brief: interjections!

Anything can be an interjection if you punctuate it correctly. Airplane! See how that works?

And how lovely to discover that holla was a word in the Victorian lexicon! Though it had a completely different meaning, which puts it in company with other migratory words like gay and nice. Oh, language, with its twists and turns.

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 6

The three words I'm considering are as follows (and I quote): drink, drank, drunk. Early in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Ford Prefect is warning Arthur Dent that hyperspace jumps are unpleasantly like being drunk. Arthur asks what is so unpleasant about being drunk -- Ford replies: "You ask a glass of water."

The joke hinges on the confusing nature of certain irregular English participles. A participle is the form of the verb that can be used as part of a compound verb, or as an adjective. The participle of the verb be is been, as in I have been confused. Most often the participle in English is identical to the past tense: I have walked to the store. But in certain cases, where the word has a long history and frequent usage -- verbs like be, do, get, eat, think, all the basic verbs human beings use all the time because human beings are almost always being, doing, getting, eating, or thinking something -- you get irregular participles.

And when you get irregular participles, you get confusion. I swim, but have I swam or have I swum?

Current grammatical common sense declares that drank is the past tense and drunk is the participle. Last night I drank some wine/Last night some wine was drunk by me. But drunk can also be used as an adjective as well as the past tense of the verb -- in fact, this problem has been confusing native and non-native English speakers for centuries now.

The Practical deals with this problem in an incredibly snobbish manner:

The Practical is an arch-suck-up, and only the writings of respected (white, male, usually dead) authors (who may be attempting to sound archaic on purpose) count. There is quite a list, as though Noble Butler wants to overwhelm you by sheer quantity of evidence:

Incidentally, my very favorite participle in English is quite rare and getting rarer. It is dolven, the past participle of delve. As in: This mine shaft was dolven in 1902.

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 5

For the first time in this experiment, I find myself relieved to agree with the Practical, and on no less a subject than the passive voice:

The passive voice is often talked about, but rarely defended. This is a travesty. I am uncommonly fond of the passive voice, because it is important and useful. The difference between the example sentences above is a nuance, but one of the best things about language is its ability to convey very fine shades of distinction. Telling beginning writers/students to avoid the passive voice as though it is the writerly equivalent of a cravat or corset is leaving out a very useful technique. It is one of the many things that makes me grumpy when I read George Orwell.

Orwell's objection to the passive voice is that it allows the result to stand out more than the agent.  So that instead of saying, "I screwed up," a politician might say, "Mistakes were made." And there is some truth to that. But there is also a case to be made for keeping the passive voice, even in political speech. For instance: the celebrated phrase: "all men are created equal." There's your passive voice right there. The Declaration of Independence is a far from passive document, and this phrase more than any other has become an axe to wield against anything resembling inequality (as opponents of gay marriage are in the process of finding out). And though it goes on to mention that men are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, it is not the Creator or the question of his existence that is important in this passage. It is people. For this reason, it is stronger and clearer to say that men are created or are endowed, since through the passive voice it becomes an existential condition. Man is a creature with rights.

So that instead of saying, "I screwed up," a politician might say, "Mistakes were made." And there is some truth to that. But there is also a case to be made for keeping the passive voice, even in political speech. For instance: the celebrated phrase: "all men are created equal." There's your passive voice right there. The Declaration of Independence is a far from passive document, and this phrase more than any other has become an axe to wield against anything resembling inequality (as opponents of gay marriage are in the process of finding out). And though it goes on to mention that men are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, it is not the Creator or the question of his existence that is important in this passage. It is people. For this reason, it is stronger and clearer to say that men are created or are endowed, since through the passive voice it becomes an existential condition. Man is a creature with rights.

For contrast, imagine this sentiment in the active voice: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that God created all men equal, that the Creator endowed them with certain unalienable Rights. Man -- political, democratic, revolutionary man -- has all but disappeared from the text. He goes from the verb's subject to its object. And despite the presence of the word unalienable, it stands to reason that if God endows you with something, he could just as well un-endow you if he ever felt like it.

As is, strangely, the passive voice becomes the stronger voice, the voice that lets man take an active role in the creation of a new system of government.

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 4.

Time to talk participles! From the Practical:

(As a side note, how often do you think this male-active/female-passive paired structure crops up in this text? Frequently! It can be a little infuriating.)

Finally -- finally! -- we get explicit confirmation that Noble Butler looks upon his grammar as an attempt to scientifically classify the words of the English language.

Note how he cites Bacon, even though Origin of Species had already done its bombshell work on scientific thinking at the time of Butler's publication. Butler is non-Darwinian in his approach to taxonomy. For instance, this sentence: "To allow words to dodge from one class to an other, is not only unphilosophical, but ridiculously absurd." Butler is trying to set down the rules for the proper behavior of English -- which, as we have seen, requires a thorough philosophy of the categorical differences between men and women, animals and plants, people and animals. This refusal of allowing words to migrate form -- as though the rules of language were all thought up at once in systematic fashion -- is the product of an insecure and tyrannical mind. Butler wants to control English as a language because then he can control the beings the words represent. Reality is to be subject to philosophy, and to the common sense of the educated white Victorian male. The idea that nouns could become verbs is as anathema as the idea that primates can become people.

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 3

One of the most surreal aspects of the Practical is its long passages of sample sentences. After a time, they begi to read like the finest surrealist literature. Take this paragraph, from the section on verbs: Our pastoral scene in the beginning (horse, stable, corn) gives way to an apparent family drama in the vein of William Faulkner (Robert's glance, smoke, knives, parched earth). There is a sudden and inexplicable threat from nature (a tiger!) which is just as inexplicably dispatched (the serpent crushes the tiger!). We are left with matters unresolved (the bird on the fence).

The next paragraph:

The destructive violence of pagan Rome (Brutus, Mummius) gives way to the wonder of creation and the iron hand of George Washington. Birds and water in the next sentences seem to indicate the utopian ideals of the young American country on the morning of its birth, which is supported by the upright moral tone of the good man avoiding vice. The boy's stumble, the woman's sins, and the mud, however, indicate that this perfect project has become less than idyllic, even as the final sentence implies that those utopian ideals are still the goal (up the hill).

The strangest of all:

Again, the pastoral (mother, oxen) gives way to something darker (one man's debt and another's wealth). The turning wheel of the boy indicates the wheel of fate, a change in each character's position. Now it is the other man who is rich (possesses a large estate). The boy's fire is an omen of danger, of this John who has sinister plans that our narrator is prescient enough to uncover. Despite this knowledge, our narrator fails in his confrontation with John, and the last sentence on the price of the book -- the book you are holding in your hands as you read this, perhaps? -- indicates just how far he has fallen in the course of the narrative's unfolding.

Supposedly, of course, there is no connection between these sentences. They are grammatical exercises, meant to help the reader become comfortable with picking out the verb and its subject. But the fact that they are placed in paragraphs confuses the matter a little bit. If they were listed out, it would not feel so much like a story. But in paragraphs, you start to assume there must be an inherent connection between the scenes that unfold. Otherwise, how would you know where to put the paragraph breaks? Why not have just one long text block?

Somehow, this section on verbs gets near the heart of storytelling without realizing it. The Practical likes to think of itself as being clear and concise and rigid. Everything can be put into a box, classified and categorized and labeled to within an inch of its life. But then in the verb section, the reader is present with the following exercise:

Suddenly it is time for Victorian Mad Libs.

Verbs really are the heart of story. You can leave out almost any other part of speech -- adjectives and adverbs in particular, according to every piece of writing advice everywhere -- but you have to have the verbs, even if they're abstract and otherworldly things like think or worry or imagine. Even Victorian Mad Libs, with its collection of the world's most mundane nouns, can't protect itself from the potential of becoming either a stomach-emptying gore-fest (The dog exsanguinated on the grass) or a Proustian philosophical narrative (Time reverses swiftly) or anything else you like.

NGD Preparatory Academy, Vol. 2

In my last post I talked about grammatical gender, which is pretty straightforward even for us gender-impoverished Anglophones.

Today, we enter the slightly more terrifying world of case. From the Practical:Put simply, case is the difference between the words I and me. I is in the nominative, which simply means it is the subject of a verb: I believe I can fly. Me is the objective case, which means it is the object of a verb: Fly me to the moon. To move from I --> me is to decline a noun, and declension is the complete list of forms a noun in a particular language can take.

We Anglophones are somewhat lucky that in modern English very few words are actually declined. At this point, you will be wondering why on earth I think this tiny and forgotten quirk of the language is interesting. Cases are boring, you are thinking. You are so completely wrong. Cases are the opposite of boring. They are terrifying.

What cases do* is encode the grammatical function of the word into the way it is spelled. Ancient Greek has four of them and uses them constantly. Latin, not to be outdone, has five. So the declension for the Latin word murus, which means wall, looks like this:

murus, muri, muro, murum, muro.

And in the plural:

muri, murorum, muris, muros, muris.

All these mean wall, but which one you use will depend on precisely what you are trying to say about this wall. But wait! you say. Some of those look the same! How do I know if the muri I see is a genitive singular or a nominative plural? The answer: you really don't. Context is usually helpful, but not always.

What this means: Latin will kick your ass if you look at it funny. It means that ambiguity is built right in, so each conversation or text is laced with grammatical minefields. And, my favorite part, it means that a lot of times you can take a sentence, shuffle the words around, and still make sense.

In fact, you can make a sentence that means two things at once, a sentence which contradicts itself in a clever way that you can never quite collapse into a singular idea. For instance, this first line from a poem of Catullus: Ille mi par esse deo videtur. Catullus is citing in Latin one of the most famous of Sappho's poems in Greek, and so readers in the know translate the line thus: He seems like a god to me.

But if you look at the words in strict order, you get this: He to me equal being to god seems. Note how to me and equal are close together, and how close to god is to seems. Because to me and to god are in the same case, there is no grammatical reason why this line cannot be translated as: He seems to god to be equal to me. Or even: He seems to be equal to me -- and I am a god. And if you try to resolve it by saying that me is not in the dative case (like god) but is an ablative (which would be identically spelled), then you get something else altogether: either He to my disadvantage seems equal to the gods, or He to god's disadvantage seems equal to me.

The word order in Sappho's poem is much clearer: It seems to me that he is equal to the gods. The plural gods prevents the line in Greek from the ambiguity of its Latin equivalent. Both Sappho's and Catullus' poems are about love triangles, about being so overwhelmed by the beloved that you can't even talk about her, but have to talk about the man sitting next to her at a party. Sappho's poem is a despairing sigh, but Catullus' tricksy word order embodies the struggle against the romantic rival within the grammatical structure of the line. Neither the love triangle nor the word order can be simplified or resolved.

A British study not too long ago found that Shakespeare's grammar tended to prod the human brain into a slightly more excited state, partly because it became a puzzle the brain constantly had to solve in a satisfying way. Latin poetry is like Shakespeare on steroids.

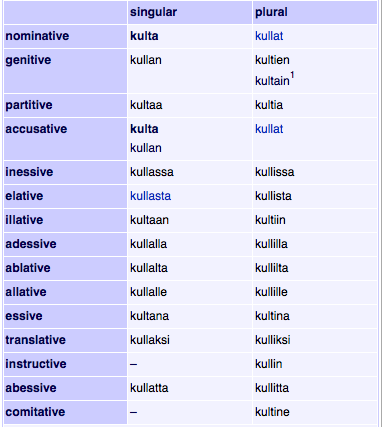

And this is just using two (or maybe three) of a modest five cases. Some languages have many more. Finnish, for instance, has fifteen of the things. For every Finnish word there are fifteen different ways to spell it, and another fifteen ways to spell the plural form. If you are inside the car, the auto, you are autossa. If you are getting out of the car, you are autosta. If you are sitting on top of the car, you are autolla, or falling off the top of the car, autolta. (The geographic specificity of many Finnish cases might explain why the Finns are so damn good at architecture. They're always thinking in terms of where something is.) The declension of the Finnish word kulta, which means either gold (the metal) or darling (the person), looks like this:

You'll notice the way the -lt- changes to -ll- sometimes for no apparent reason. This is something Finnish does just to mess with foreigners.

Be grateful, Anglophones, that all we have to think about most days is what the damn words mean.

* At least, this is what cases do in the Western languages that I have had the opportunity to study in depth. If anyone with a good working knowledge of Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Thai, or anything else wants to chime in and correct me, I will be delighted.

National Grammar Day Preparatory Academy, Vol. 1

Did you know we have a National Grammar Day? It is true. It seems we have all manner of National Days lately, though I haven't yet tracked down which government office is ultimately responsible for the proliferation of Days. When I do, I fully intend to send them a card.

The point is this: National Grammar Day is on March 4, and March 4 is fast approaching. Steps must be taken. Can we really expect to wallow happily in the mud of English usage for a mere twenty-four hours with no preparation? Of course not! Rash to even consider it!

The point is this: National Grammar Day is on March 4, and March 4 is fast approaching. Steps must be taken. Can we really expect to wallow happily in the mud of English usage for a mere twenty-four hours with no preparation? Of course not! Rash to even consider it!

With that in mind, every other day from now until National Grammar Day, I will be sharing my commentary upon tidbits from Noble Butler's A Practical and Critical Grammar of the English Language (1874). This book is dense, and coolly angry. Many footnotes take up more than half a page. It is obsessively taxonomical, and approaches English as though it were a rare and precious species of butterfly that must be thoroughly anaesthetized before being put on display in a quiet room somewhere out of direct sunlight with a shiny pin through its once-beating heart.

What fun!

Let us start with gender. Many of you are under the impression that we have no grammatical gender in English. According to the Practical, you are wrong:

I apparently have no gender, nor does my parent. Or, it seems, that sheep -- and maybe I'm the only one who finds the sequence parent-cousin-sheep-I-who a little bit hilarious. I am left wondering what the next word might be.

The Practical goes on to state that some classes of nouns "have no common gender, but only those which denote males and females." The example? Horse. Horse, it seems, is masculine, in contrast with mare. Apparently Noble Butler has never heard of either a stallion or a gelding. The Practical's advice for such nouns is either use both (brothers and sisters), circumlocute (children of the same parents), or:

Men get horses, and women get geese. Does that strike anyone else as a little unfair?

Lest you think I am reading unnecessary bias into this starchy Victorian tome, the following passage helpfully clarifies:

The upshot: speaking proper English requires having a full set of gender stereotypes in place before you even open your mouth.

Not Enough Swear Words

Ladies and gentlemen, I am sorry to say that my hard drive burned itself out today like a disco queen on laced cocaine. The love of my life was kind enough to loan me his computer until I can get mine resurrected or reincarnated, so at least I can keep writing and playing games on the internet -- oh, Prolific, my life's blood -- but even though very little is lost it still feels crushing and catastrophic.

I remember the first time I lost a story. It was summer, and I was about fifteen or so, and I had this whole huge fantasy teen romance based on Cinderella that I was very excited about and very carefully inscribing in a notebook. Invading kingdoms, false identities, magic wands -- it was intricate, I tell you, and I can't remember the half of it. And because I couldn't bear to leave it alone even for the space of a week, I took it with me on our yearly eastern Washington camping trip.

As part of this trip, we went to a water park in the middle of a wide stretch of desert, which wasn't quite as hedonistic as the indoor skiing area in Dubai but was as close as teenaged me was likely to get. When we returned to the car, I peeked in and thought it was strange that the backseat was covered with ice when it was so hot out. And then Mom started fretting and I realized that no, it wasn't ice -- it was the glass from the window of the car. Some very unsubtle criminal had busted in the window and taken -- well, I don't remember the details of what they took except that it included my backpack, a very expensive-looking hiker's pack they must have thought was full of God knows what. What it actually contained was my story notebook, the Everyman's Library edition of Jane Eyre, and about fifty Always brand ultra-thin feminine hygiene products with Flexi-wings (TM) that I earnestly hope they enjoyed.

And there I stood, feeling sick to my stomach, and not just because I now had to publicly announce why we needed to stop by a grocery store on the way back to camp.

The second time I lost stories, it was because a computer was stolen. By this time I was out of college and living in what may be charitably called a dump of a house in Seattle's University District. One of my housemates asked to borrow my computer to check his email when I went to bed, and I acquiesced. In the morning, I noticed it was not on the couch where he usually left it after such incidents, but I was running late to work and thought nothing of it. When it failed to reappear after a thorough search when I came home, I gave my housemate a call.

"Have you checked under the couch cushions?" he asked. As though a lost computer were the equivalent of paperclips and fuzz-covered mixed nuts. I told him no, yelled for a little while, and then called the police who were very polite when they showed up six hours later.

This was rougher than the first time: the stolen computer had contained all my undergraduate academic work as well as the just-for-fun things I'd managed to jot down along the way. (Three words: "Jane Austen's Medea.") I couldn't seem to stop crying. To this day I entertain paranoid fantasies that the girl this housemate was hooking up with at the time -- and who left for a study-abroad quarter in Berlin the very next day -- had been the one to steal it.

The third time was two years ago, when a software update automatically installed itself, froze the computer, and blitzed the hard drive when I attempted in my ignorance to reboot. Something about the fresh-faced superiority of the Apple Genius Bar can really bring the shame home like nobody's business, believe you me.

Today's computer death marks the fourth time I've lost things half-finished and tentative, and strangely it has made me both angry and energized. If fate decrees a fresh start, then damn it I'm going to fresh-start it like you've never seen it fresh-started before. I might try and rewrite the whole thing without even looking at the now-very-altered second draft of the story that's been giving me trouble. You think that's crazy? Probably -- but watch me!

See that, technology, you fickle and frustrating beast? You can slow me down, and make me cry, and make me swear in chains of curse words like the DNA of some vast and complicated chimera, but ultimately you cannot win. And if I still fail, at least I'll fail on my own terms.