In my last post I talked about grammatical gender, which is pretty straightforward even for us gender-impoverished Anglophones.

Today, we enter the slightly more terrifying world of case. From the Practical:Put simply, case is the difference between the words I and me. I is in the nominative, which simply means it is the subject of a verb: I believe I can fly. Me is the objective case, which means it is the object of a verb: Fly me to the moon. To move from I --> me is to decline a noun, and declension is the complete list of forms a noun in a particular language can take.

We Anglophones are somewhat lucky that in modern English very few words are actually declined. At this point, you will be wondering why on earth I think this tiny and forgotten quirk of the language is interesting. Cases are boring, you are thinking. You are so completely wrong. Cases are the opposite of boring. They are terrifying.

What cases do* is encode the grammatical function of the word into the way it is spelled. Ancient Greek has four of them and uses them constantly. Latin, not to be outdone, has five. So the declension for the Latin word murus, which means wall, looks like this:

murus, muri, muro, murum, muro.

And in the plural:

muri, murorum, muris, muros, muris.

All these mean wall, but which one you use will depend on precisely what you are trying to say about this wall. But wait! you say. Some of those look the same! How do I know if the muri I see is a genitive singular or a nominative plural? The answer: you really don't. Context is usually helpful, but not always.

What this means: Latin will kick your ass if you look at it funny. It means that ambiguity is built right in, so each conversation or text is laced with grammatical minefields. And, my favorite part, it means that a lot of times you can take a sentence, shuffle the words around, and still make sense.

In fact, you can make a sentence that means two things at once, a sentence which contradicts itself in a clever way that you can never quite collapse into a singular idea. For instance, this first line from a poem of Catullus: Ille mi par esse deo videtur. Catullus is citing in Latin one of the most famous of Sappho's poems in Greek, and so readers in the know translate the line thus: He seems like a god to me.

But if you look at the words in strict order, you get this: He to me equal being to god seems. Note how to me and equal are close together, and how close to god is to seems. Because to me and to god are in the same case, there is no grammatical reason why this line cannot be translated as: He seems to god to be equal to me. Or even: He seems to be equal to me -- and I am a god. And if you try to resolve it by saying that me is not in the dative case (like god) but is an ablative (which would be identically spelled), then you get something else altogether: either He to my disadvantage seems equal to the gods, or He to god's disadvantage seems equal to me.

The word order in Sappho's poem is much clearer: It seems to me that he is equal to the gods. The plural gods prevents the line in Greek from the ambiguity of its Latin equivalent. Both Sappho's and Catullus' poems are about love triangles, about being so overwhelmed by the beloved that you can't even talk about her, but have to talk about the man sitting next to her at a party. Sappho's poem is a despairing sigh, but Catullus' tricksy word order embodies the struggle against the romantic rival within the grammatical structure of the line. Neither the love triangle nor the word order can be simplified or resolved.

A British study not too long ago found that Shakespeare's grammar tended to prod the human brain into a slightly more excited state, partly because it became a puzzle the brain constantly had to solve in a satisfying way. Latin poetry is like Shakespeare on steroids.

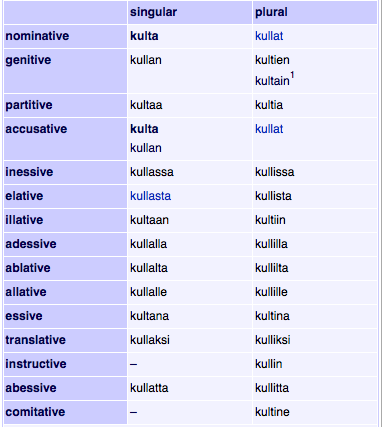

And this is just using two (or maybe three) of a modest five cases. Some languages have many more. Finnish, for instance, has fifteen of the things. For every Finnish word there are fifteen different ways to spell it, and another fifteen ways to spell the plural form. If you are inside the car, the auto, you are autossa. If you are getting out of the car, you are autosta. If you are sitting on top of the car, you are autolla, or falling off the top of the car, autolta. (The geographic specificity of many Finnish cases might explain why the Finns are so damn good at architecture. They're always thinking in terms of where something is.) The declension of the Finnish word kulta, which means either gold (the metal) or darling (the person), looks like this:

You'll notice the way the -lt- changes to -ll- sometimes for no apparent reason. This is something Finnish does just to mess with foreigners.

Be grateful, Anglophones, that all we have to think about most days is what the damn words mean.

* At least, this is what cases do in the Western languages that I have had the opportunity to study in depth. If anyone with a good working knowledge of Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Thai, or anything else wants to chime in and correct me, I will be delighted.